For the latest information on remediation of the Greenpoint Oil Spill please visit the official DEC website here.

—————

Discovery

At noon on October 5th, 1950 a reinforced concrete sewer exploded in the heart of Greenpoint blowing manhole covers three stories high, shattering shop windows, injuring three persons, and ripping open a ten foot section of pavement at the intersection of Manhattan Ave. and Huron.[1]

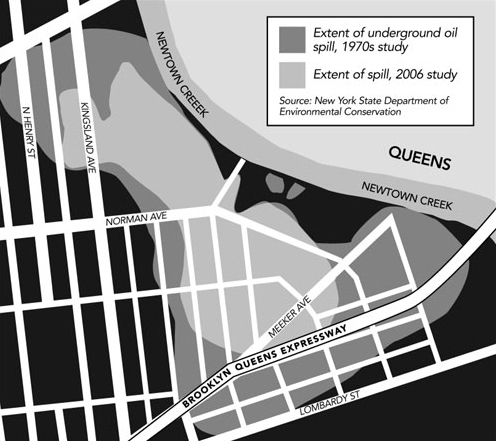

Unbeknownst to investigators at the time, the explosion was the first indication of the massive oil spill lurking under Greenpoint. The full dimensions of the spill would remain a mystery until 1978, when during a routine patrol the Coast Guard noted an enormous plume of oil streaming down Newtown Creek from the end of Meeker Avenue.

Subsequent study would pin the oil spill at between 17 and 30 million gallons (an amount at least 50% bigger than the infamous 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill) several feet thick in some places, and just a few feet below the surface in others.[2] The plume was estimated to course below 55 acres of Greenpoint industrial, commercial, and residential property effecting hundreds of homes and dozens of businesses.

Research has determined that ExxonMobil, Chevron/Texaco, and BP refining operations leaked the oil and refining products into the soils and aquifers of Greenpoint over the course of decades.[3] The oil spill is not the result of one distinct event but the toxic culmination of 140 years of spillage. Since 1978, approximately 12.9 million gallons of oil and oil products have been recovered from the soils beneath Greenpoint and the waters of Newtown Creek (as of March 2017).

Responsible Parties

Those properties which contributed to the oil spill have traded hands many times over the years and the oil companies who are responsible have all consolidated into new entities. Mobil became ExxonMobil, Amoco was bought by BP, and Paragon is now part of Chevron/Texaco. These companies now legally inherit the environmental legacy of their predecessors. Some of the current tenants of the original leaky properties include: BP (Apollo St. and Norman Ave.), Peerless Importers (16 Bridgewater St.), and Long Island Carpet Cleaners (301 Norman Ave.).

Cleanup, Lawsuits, and Legislation

Mobil set up oil recovery operations in 1979, approximately one year after the Coast Guard discovered the oil spill. Unfortunately, the scale of the remediation effort was disproportionately small compared to volume of oil spilled, and the cleanup showed little progress over the course of the 1980’s. Adding insult to injury, Mobil spilled an additional 50,000 gallons of oil into Newtown Creek and Greenpoint during one winter week in 1990. This event led the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to negotiate a new cleanup plan with Mobil, however, weak enforcement and regulation continued to be the rule, making continued delay a favorable tactic.[4]

By 1995 Mobil had installed new pumps and by 2005 the responsible parties had extracted between a quarter or half, depending on one’s estimate, of the total oil. In 2004, in an effort to accelerate the cleanup and address the injustices of previous agreements between DEC and ExxonMobil, Riverkeeper filed suit against ExxonMobil for violating the Clean Water Act and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. This undoubtedly turned up the pressure on DEC which has subsequently pursued a more stringent cleanup.

In July 2006 the President signed the Coast Guard and Maritime Transportation act of 2006, which among hundreds of other things, authorized the first ever “independent” public health and safety study of the Greenpoint Oil Spill.[5] The “study”, conducted by Lockheed Martin under contract with the Environmental Protection Agency, was released in September 2007 and is more accurately described as a review of reports since no original research or testing was performed. With the exception of the 1978 Geraghty & Miller study conducted at the behest of the Coastguard in 1978, all of the data and information analyzed in the report comes from documents generated by the principal responsible parties, i.e. consultants to ExxonMobil, BP, and Chevron/Texaco.

In February 2007, The Attorney General’s Office, with a newly elected Andrew Cuomo at the helm, filed a notice of intent to sue against ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, Keyspan and Phelps Dodge for violating the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act by “creating an imminent and substantial endangerment to health and the environment in Newtown Creek and portions of the adjacent shoreline.”[6]

In January 2007, Riverkeeper again filed a notice of intent to sue against ExxonMobil, joined by the Attorney General’s office, for their failure to properly treat the oil-stripped groundwater they were pumping out and discharging into Newtown Creek.[7] In March 2007 ExxonMobil reacted by shutting down their recovery wells thereby reducing the daily extraction of oil from an average of 1,110 gallons a day to 87 gallons a day. After agreeing to the stricter discharge limitations and increased reporting requirements established by DEC, ExxonMobil began pumping out and treating the groundwater again in July 2007.[8]

In addition to the suits filed by Riverkeeper and the Attorney General’s office, a class action lawsuit has been filed on behalf of 300+ Greenpoint residents by Giradi and Keese (Erin Brockovich’s firm) in collaboration with the Alpert firm. The civil suit seeks tens of billions of dollars in damages from ExxonMobil, Chevron/Texaco, and BP.

Potential Exposure Pathways

Testing conducted by ExxonMobil contractor Roux Associates in the Summer of 2006 and the Summer of 2007 continues to confirm the presence of potentially explosive concentrations of methane gas [9] and dangerous levels of the cancer causing agent, benzene, in the shallow soil vapor beneath the intersection of Bridgewater Street, Apollo Street, and Norman Avenue.[10] In order to address the ignition hazard posed by methane gas escaping into the air or concentrating in underground structures and the health hazard posed by breathing in benzene vapors that have collected in buildings; ExxonMobil has committed to engineering a soil vapor extraction system that will begin operation in August of 2008. [Maps detailing the methane and benzene contamination, pdf 3.2mb] Vapor testing in the area of the oil spill conducted by NYSDEC and Roux Associates has also detected hazardous concentrations of chlorinated solvents (tetrachloroethene, aka PCE and trichloroethene, aka TCE) at four separate locations.[11] These vapors are unrelated to the oil spill but pose a significant human health risk. [For more information visit the Meeker Ave. Plumes page]

About the ExxonMobil N. Henry St Facility

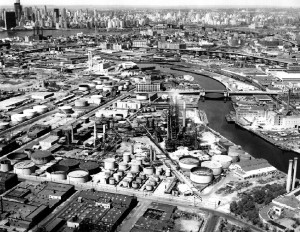

Petroleum refiners first began operating along Newtown Creek in the 1860’s and their numbers proliferated rapidly in the ensuing decades. In 1892, the majority of these refineries were purchased and consolidated into the Standard Oil Trust. Following the breakup of the Trust in 1911, ownership of the refinery and petroleum bulk storage facility located at 300 North Henry Street, the facility responsible for most of the oil now coursing below Greenpoint and spilling into the creek, reverted to the Standard Oil Company of New York, these operations later became Mobil Oil. [1954 Aerial Photo of the N. Henry St. Mobil Oil Refinery, pdf 500kb]

Historically these facilities, also referred to as the Brooklyn Terminal, included a large tank farm property (now a part of the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant) and a refinery and storage facility that encompassed all of the land now bounded by North Henry Street, Greenpoint Avenue, Norman Avenue, Apollo Street, and Newtown Creek. At its peak this facility could refine over a million gallons of crude oil a day and produced fuel oils, gasoline, and kerosene. A 1919 conflagration at the Standard Yards, as the refinery complex was then called, incinerated more than 20 acres of oil tanks. The tanks, storing 110 million gallons of oil at the time of the fire, reportedly exploded like “volcanoes”, “filling the sky with flame and smoke”.[13]

Operations at the former Mobil Brooklyn Refinery ceased in 1966 and the refinery was subsequently demolished and much of the property sold off. The lots retained by Mobil were utilized as a petroleum bulk storage terminal until 1993, when storage operations at the property ceased. Mobil merged with Exxon in 1999.

Technical Aspects of the Remediation

More than 315 monitor/observation wells and approximately 42 designated product recovery wells have been installed above the oil spill since 1978, only a fraction of these wells are still actively recovering oil. As the cleanup has progressed and the overall plume has shrunk in area, certain recovery wells were removed from service, while others were added to optimize product recovery. In this system, a lower pump withdraws ground water, creating a cone of depression in the groundwater system; a second pump, placed at a shallower depth in the well, removes the induced product that is floating on top of the water column. Because both water and product are recovered from a dual-pump system, treatment and/or disposal is necessary for both fluids.[14]

All the oil cannot be removed by recovery well and a certain amount of residual product will remain trapped in the soil pore spaces. The residual oil cannot be mobilized by pumping because the small individual oil pockets are held in place by capillary pressure and become disconnected. Thorough remediation will require other technologies such as injection of surfactants or biological remedial compounds, bioslurping, vacuum enhanced recovery, steam or hot water injection, and electrical heating.

From 1993 through mid-2005, Exxon/Mobil collected approximately 29,000 gallons of free product from Newtown Creek, primarily through the use of containment booms and free-product skimmers. Since 2005, Chevron/Texaco has taken over the remedial activities at the Peerless Importers site where oil leaked from beneath Greenpoint directly into Newtown Creek. Remedial activities along the Creek have involved seep containment using a boom system and product removal by extraction from several monitoring wells immediately landside of the steel bulkhead. In March 2006, oil was noticed seeping into Newtown Creek behind the Steel Equities property at 110-120 Apollo Street; in response Chevron/Texaco installed an additional 100 feet of hard and soft booms. In addition, a grout wall was completed in November 2006 immediately landside of the entire bulkhead frontage to impede the migration of product into Newtown Creek.

Summary of Recommendations from 2007 EPA Report

(o) A comprehensive area-wide feasibility study that includes coordination among all responsible parties is needed. NYSDEC appears to be working toward this goal, but competing interests among the multiple responsible parties hinder this effort.[15]

(o) The original 17 Mgal product volume estimate should be used with caution. Comparison of the 8.8 Mgal product recovery volume with the apparent static size of the plume suggests that the original volume estimate may have been low, or that recovery volumes are optimistic, or both.

(o) A reevaluation of remaining plume volume across the entire project area, using corrected product thickness values, is warranted.

(o) Additional monitoring wells need to be installed to delineate the northern portion of the plume.

(o) Additional geologic investigation in the area of the Exxon/Mobil On-Site plume appears warranted. This area exhibits the thickest product accumulations, but also the lowest product recovery rates.

(o) Because monitoring wells within the plume area are likely to be affected by variations in the water table, an ongoing effort should be made to monitor an existing observation well and study the long term ground water levels.

(o) Other remedial technologies (e.g., injection of surfactants or biological remedial compounds, bioslurping, vacuum enhanced recovery, steam or hot water injection, and electrical heating) should be considered for recovering additional product once the bulk of the free-product is recovered.

(o) Naphthalene should be added to the analytical suite of subslab sampling data.

(o) NYSDEC should investigate and collect additional data on the extent of the dissolved plume. Very little data have been collected to date in reference to the dissolved phase of the plume.

(o) NYSDEC should make readily available a decision matrix/flowchart for the Greenpoint community that clearly explains how data are being evaluated and how risk management decisions are being made regarding subslab, indoor, and ambient concentrations.

(o) NYSDEC has and should continue to attempt to get access to additional homes along Kingsland Avenue, Van Dam Street, Meeker Avenue, and South of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway (BQE) for further subslab and indoor air sampling to close existing data gaps.

(o) NYSDEC should continue outreach to commercial facilities which are located within the residential areas (delicatessens, shops, etc.) to get access, so that vapor intrusion data can be collected.

(o) NYSDEC should continue to evaluate ground water data for both the free product plume and the dissolved phase plume to determine if boundaries of the vapor investigation should be revised.

(o) NYSDEC should evaluate its ambient air monitoring program to investigate potential confounding sources to indoor air.

(o) NYSDEC should evaluate existing databases for background air concentrations in similar communities for comparison against the Greenpoint community.

Learn More

NYSDEC: The NYS Department of Environmental Conservation can answer any questions you may have regarding cleanup and enforcement. Visit the “Greenpoint Petroleum Remediation Project Public Website” for additional information. DEC also maintains an extensive online document library detailing the remediation efforts to date and the vapor intrusion and indoor air sampling results.

Riverkeeper: The organization that put a public spotlight on the oil spill.

Girardi and Keese: The law firm pursuing the civil suit against ExxonMobil, BP and Chevron has an extensive website covering the oil spill.

Footnotes

1. The New York Times. October 6, 1950. “Greenpoint Rocked by Sewer Explosion”. And, The New York Times. October 10, 1950. “Still Seek Brooklyn Gas Leak”.

2. EPA. September 12, 2007. “Newtown Creek/Greenpoint Oil Spill Study: Brooklyn, New York”

3. EPA. September 12, 2007. “Newtown Creek/Greenpoint Oil Spill Study: Brooklyn, New York”

4. New York City Council Committee on Environmental Protection. “Update on Progress at the Newtown Creek/Greenpoint Oil Spill Remediation Site”. November 26, 2007.

5. Anthony D. Weiner’s Office. Press Release. July 27, 2006. “Congress Authorizes Study of Nation’s Largest Oil Spill”.

6. Office of the New York State Attorney General. Press Release. February 8, 2007. “Attorney General Andrew Cuomo to Sue ExxonMobil in Landmark Case to Clean Up Catastrophic Greenpoint Oil Spill and Newtown Creek Contamination”.

7. Riverkeeper. Press Release. January 25, 2007. “Greenpoint Watchdogs Initiate New Action Against ExxonMobil”.

8. NYSDEC. Press Release. June 28, 2007. “DEC: ExxonMobil to Restart Cleanup at Greenpoint: Pumps To Operate Under Stricter Rules”.

9. EPA. September 12, 2007. “Newtown Creek/Greenpoint Oil Spill Study: Brooklyn, New York”. p. 7. “High levels of methane gas concentrations have been found during vapor intrusion sampling in some commercial establishments. These levels were found to be above the Upper Explosive Limit (UEL).”

10. Prepared by Roux Associates for ExxonMobil. “Soil Vapor Investigation Report: Greenpoint, Brooklyn, New York”. February 6, 2006. (pdf, 10.8 mb). And, Prepared by Roux Associates for ExxonMobil “Phase II Soil Vapor Extraction Pilot Study: Greenpoint, Brooklyn, New York”. August 14, 2007. (pdf, 3.42 mb).

11. Prepared by Roux Associates for ExxonMobil. “Soil Vapor Investigation Report: Greenpoint, Brooklyn, New York”. February 6, 2006. (pdf, 10.8 mb). And NYSDEC. “Greenpoint Petroleum Remediation Project (Off-Site Plume Area) Vapor Intrusion/Indoor Air Sampling Report for the 2006/2007 Heating Season: Site No. S224087, Brooklyn, New York”.

12. Corborn, Jason. “Street Science: Community Knowledge and Environmental Health Justice”. 2005. MIT Press. See Ch. 3 “Risk Assessment, Community Knowledge, and Subsistence Anglers”.

13. The New York Times. September 14, 1919. “Twenty Acres of Oil Tanks Ablaze. Big Factories Burn: Flames Cross Newtown Creek From Standard Yards Storing 110,000,000 Gallons of Oil”.

14. EPA. September 12, 2007. “Newtown Creek/Greenpoint Oil Spill Study: Brooklyn, New York”.

15. EPA. September 12, 2007. “Newtown Creek/Greenpoint Oil Spill Study: Brooklyn, New York”.